Each ACO identifies how it will improve care for their Medicare beneficiaries, typically through primary care initiatives such as facilitating teamwork and communication among all providers treating Medicare patients, reducing hospital readmissions, avoiding unnecessary emergency department visits and improving patients’ ability to adhere to their treatment plans. According to CMS, the total shared savings for the program was $2 billion in 2021.

There are currently 456 ACOs corresponding to 10.9 million Medicare beneficiaries. Of these, 132 ACOs are operating under the ACO REACH model, encompassing 131,772 health care providers serving an estimated 2.1 million beneficiaries, according to the CMS.

The new model enables each ACO to identify how they will reduce health disparities among the Medicaid patients they serve using tailored tactics, according to Sheehy.

“In addition to the benchmark adjustment related to the ADI, ACO REACH requires ACOs to produce a health equity plan that describes how underserved beneficiaries will be cared for under the plan. UW Health’s participation in ACO REACH really allows us to focus on advancing health equity in our community in a new and important way,” Sheehy said.

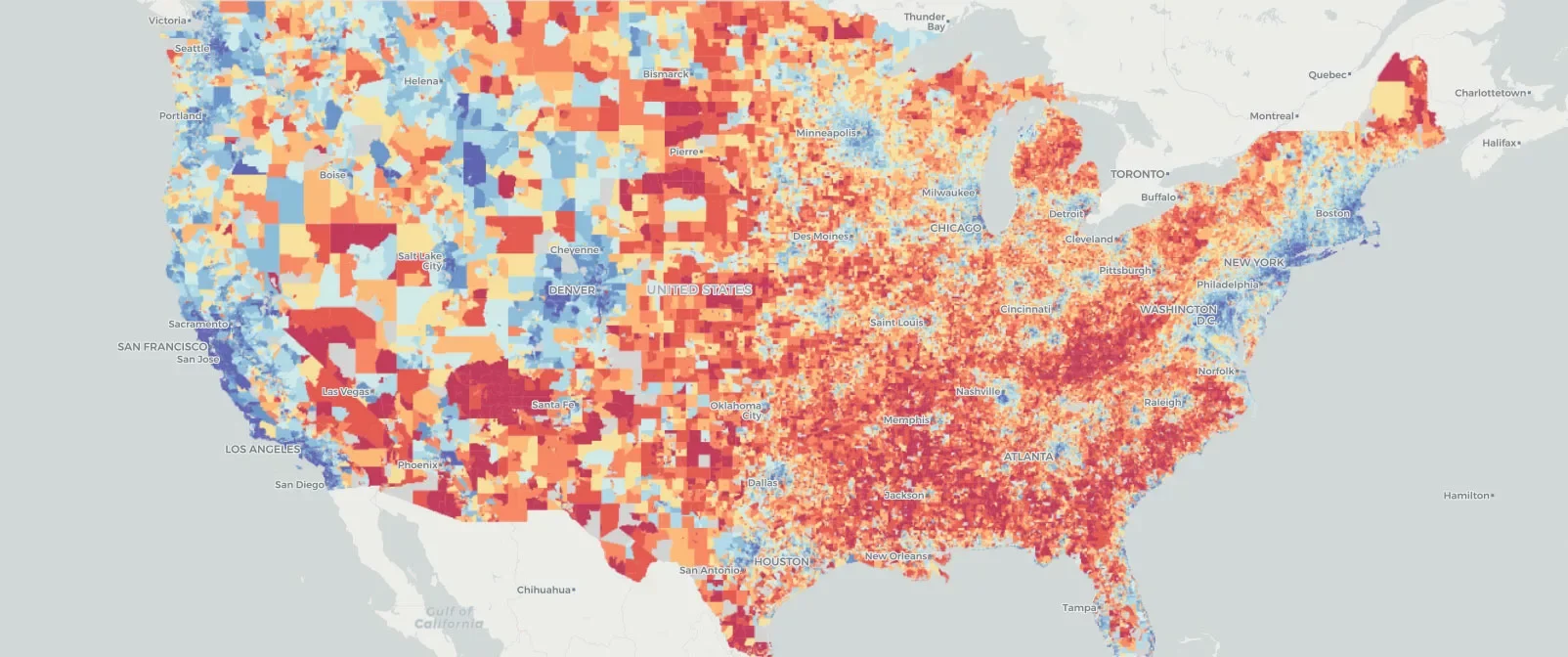

The UW–Madison researchers only learned that CMS would use the Neighborhood Atlas in ACO REACH when the model was announced by the agency. Kind’s team decided in 2018 to make their data tool widely accessible, resulting in broad uptake and uses by researchers, organizations, municipalities, public health units and state and federal agencies.

“In just five years, the Atlas has been downloaded more than half a million times, and hundreds of research studies have cited the Atlas. Sharing this resource has the potential to advance health equity across the country in ways that would not otherwise have been possible,” Sheehy said. “To have a federal agency select our UW–Madison tool to advance health equity throughout the country is truly the Wisconsin Idea at work, but on a national scale.”